Vade Mecum: Reimagining a 14th-Century Bat Book

by Bryn Michelson-Ziegler, Associate Curator & Manager of Public Programs

Associate Curator Bryn Michelson-Ziegler displaying facsimile of MS 1004/29

This year, in lieu of a proper Halloween costume, I decided to recreate one of the Rosenbach’s strange and wonderful objects, a 14th-century physician’s almanac and belt book [MS 1004/29], known affectionately as “the bat book.”

Affixing a book to one’s belt was a popular Medieval practice. Although surviving examples of these marvelous little books are rare, their prevalence can be seen in many works of art. Take the two portrayals of Saint Anthony below, by Martin Schongauer (ca. 1450-1491) and Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) respectively. In each, Saint Anthony wears a book. These artworks depict a style of belt book commonly termed a “girdle book” and used for devotional texts. They feature extended covers of soft leather that tuck into the belt. These long covers allowed the book to swing upward and be opened at any time, meaning that while worn, the top of the book points to the ground. This seems at first counterintuitive, but it’s perfect for ease of reading–think of your phone in your hand. When you drop your hand to your side after reading a text, the top of the phone faces down. A belt book is much the same.

Martin Schongauer (ca. 1450-1491), The Temptation of St Anthony. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), The Temptation of St Anthony. F. van Lanschot Collection, ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

For a belt book to be a bat book, it needs to have a few additional features. First, a bat book is assembled with a unique tabbed binding (more on this later). It is then attached to the belt or carried via cords, metal hardware, or a combination of both. Second, the pages of a bat book must be folded.

In the 2016 publication Bat Books: A Catalogue of Folded Manuscripts Containing Almanacs or Other Texts, author J. P. Gumbert describes how he coined the term: “For myself I have gradually grown accustomed to calling them ‘bat books,’ because when in rest they hang upside-down and all folded up, but when action is required they lift up their heads and spread their wings wide.”

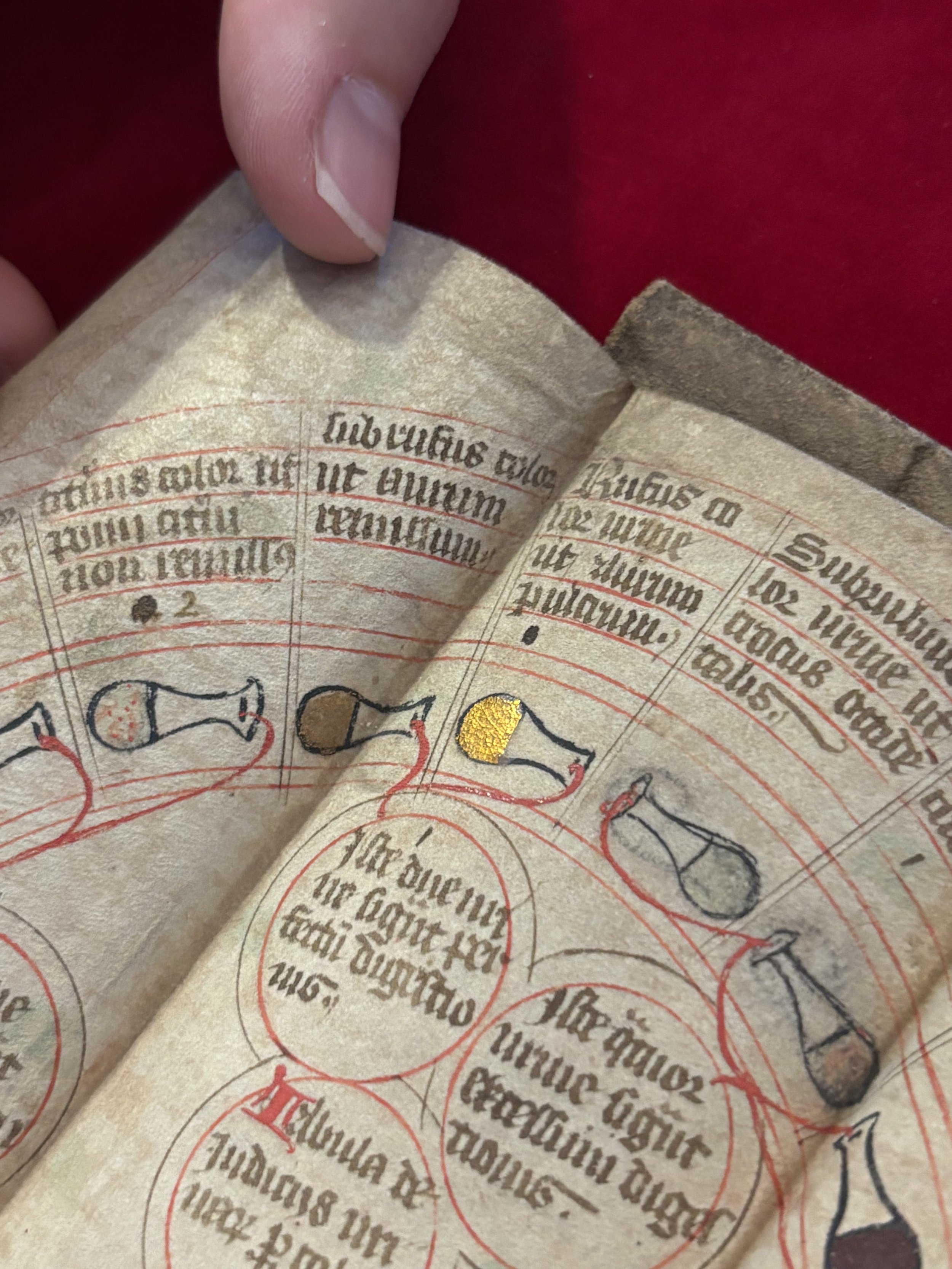

Each leaf of the Rosenbach's bat book has six compartments, as seen in the photo below. This expanding structure is ideal for fitting large, detailed, and potentially unwieldy charts that one might wish to reference frequently into a comparatively compact volume.

Almanack. York, England, 1364. MS 1004/29. Librarian Elizabeth Fuller and Bryn Michelson-Ziegler practice unfolding “Eclipses solis et lune cum canon.” Image credit Karen Grossman.

Our bat book almanac is composed of ten pieces of parchment that unfurl to reveal elaborate calendars, eclipse tables, a phlebotomy reference (also known as “vein man”), and of course, a colorful urine wheel. You may also see books of this portable structure referred to as “vade mecum,” meaning “go with me,” and for good reason–it has just about everything a good physician needs to make his rounds in the 1360s! Except, perhaps, leeches.

Almanack. York, England, 1364. MS 1004/29. Detail of “Tabula Urinarum.” Image credit Karen Grossman.

Of course, ours is not the only bat book around. Gumbert lists 63 extant examples, including ours (page 141 if you’re wondering), but it’s the only one at the Rosenbach, and so it’s the bat book in our hearts.

While this bat book is stunning, its fragility makes it a challenge to interact with and share with the world. Constant folding and unfolding are notorious for exacerbating weak points in substrates like paper or parchment, and only half of one cover, now detached, survived this book’s 661-year journey to the present. We have, however, some incredible digital ways to access this volume: BiblioPhilly’s detailed images are one, and this recently recorded session of Coffee with a Codex another. But I wondered what it would be like to step into the shoes of our intrepid 14th-century doctor, and I am a great believer in the value of making as an approach to scholarship. That is the principle that underpins the creation of the Rosenbach Book Arts Center, a burgeoning space for creative exploration at the Rosenbach: hands-on investigation enhances our ability to understand and interpret rare books.

I started my bat book by designing covers. The original cover of the Rosenbach’s bat book is composed of a stiff parchment core, with an alum-tawed outer (a specially prepared leather) and an inner lining of undyed linen. The cover also retains a portion of a stitchwork border, identified as tablet weaving by Rosenbach researcher Jacqui Carey, who has made an incredible study of the textile and embroidery decoration of a bat book in the Wellcome Collection.

Almanack. York, England, 1364. MS 1004/29. Cover detail. Image credit Karen Grossman.

For my facsimile, I started with a stiff cardstock core, used veg-tanned black leather for the outer, and substituted black book cloth with gold accents for the undyed linen. While tablet weaving is not (yet) in my repertoire as a bookbinder, I incorporated a stitched border of silk thread. And, of course, I added bat wings, because if you’re going to make a bat book... you might as well make a bat book. I’d say this project is the bookbinding equivalent of a movie that bills itself as “based on a true story.”

Bryn Michelson-Ziegler’s facsimile bat book (nicknamed Alby). Front cover detail. Image credit Bryn Michelson-Ziegler.

Bryn Michelson-Ziegler’s facsimile bat book. Back cover detail. Image credit Bryn Michelson-Ziegler.

To create the interior leaves, I used the amazing BiblioPhilly images of our book, digitally laying them out back-to-back and printing on an appropriate weight cardstock. The biggest challenge I ran into was recreating the tabs necessary for binding. To make this binding possible, each leaf has a triangular tab at its base that extends beyond the fold area. These tabs, aligned and sewn together with the covers, form the binding structure of the book. This allows the pages to fold out freely, while securing them to each other. In the image above, the sewing can be seen just under the rivet. In the image below, the equivalent sewing can be seen just below the knot in the red and green cord.

Almanack. York, England, 1364. MS 1004/29. Binding detail. Image credit Bryn Michelson-Ziegler.

Cardstock, while easier to run through an inkjet printer, isn’t as sturdy as parchment, and those small tabs must hold the entire book together while folding comfortably and repeatedly. There is evidence of at least one missing page in the Rosenbach’s bat book–a tab that failed the test of time. My solution for this facsimile was to add kitakata paper, toned with a little watercolor, to each tab. Kitakata is frequently used for book repair and added strength and flexibility to the binding.

For the hanging mechanism, I took inspiration from two different extant bat books, MRR 186 at the Louvre and MS. 79 at Princeton (see binding note), using metal hardware to attach my little bat to a leather band. In contrast, the Rosenbach’s bat book shows evidence of two woven cord structures anchored in the layered tabs, where I instead placed a rivet. One, a thicker band, would likely have been used to secure the book to the wearer’s belt or girdle. The other may have been used to hold the book open during use—perhaps as our physician was pointing out to his poor patient the flask labeled "these urines signify death.” I paid homage to these woven cords in my model by adding decorative trim tape... but took another creative liberty by using it as a wrap closure.

Here is the final result! Being able to snap this book onto my belt, page through it, and more importantly, let other people page through the beauty and peculiarity of the Rosenbach’s bat book without fear, was a delight. For me, projects like this demonstrate how book art and bibliography are interrelated. To make something is necessarily to understand it better.

Bryn Michelson-Ziegler demonstrates how the bat book facsimile is worn.

I’d like to close with a dedication to the late book artist and conservator Pamela Spitzmueller. A selection of Pamela’s book projects were exhibited at the University of Iowa Library during the Guild of Book Workers’ annual Standards of Excellence in Hand Bookbinding seminar last month. Included in the display was this stunning girdle book model and this charming hand-made bookbinding weight. Explore more of Pam Spitzmueller’s work in the University of Iowa Special Collections and Book Model Collection. This year, the Guild of Book Workers established a scholarship to Standards in honor of Spitzmueller. As a scholarship recipient, I hope that this project honors her legacy of artistry, hands-on research, and playfulness.

Pamela Spitzmueller (1950-2025), Blue Suede. Artist book structure, study of a girdle binding with sueded textile covering. University of Iowa Libraries BMC 20b.38. Image credit Bryn Michelson-Ziegler.

Pamela Spitzmueller (1950-2025), Clara the Rhino. Book weight. University of Iowa Libraries BMC 20d.08. Image credit Bryn Michelson-Ziegler.