James Joyce in Translation: The Case of the Japanese Edition of Finnegans Wake

by Kayla McDonald, Group Sales and Visitor Experience Manager

Group Sales and Visitor Experience Manager Kayla McDonald presents on Japanese translations of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to visitors on Bloomsday of 2025.

In honor of James Joyce’s birthday, let’s look back on a presentation from Bloomsday of 2025!

Before I took my position as Visitor Experience Manager here at the Rosenbach, I worked at Shofuso Japanese Cultural Center. I’ve studied Japanese off-and-on for about 15 years, and the more I learn, the less I realize I know. This feeling is particularly potent when diving into the Japanese edition of James Joyce’s final work, Finnegans Wake.

Finnegans Wake remains a singular pillar in not only Joyce’s oeuvre, but modern literature as a whole. Joyce started writing Wake right after Ulysses was published, though it remained a “work in progress” for 17 years. Joyce died a little over a year after its 1939 publication.

Finnegans Wake has a variety of linguistic quirks embedded in its DNA. The first sentence creates a loop with the last sentence, evidenced by the lowercase “riverrun”:

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

You may notice this is also a portmanteau—“riverrun” is not a word in the dictionary! Finnegans Wake is full of portmanteaus, deliberate misspellings, puns, and wordplay. Joyce’s intent was to create a text that was laden with subtext at the single word level. There are many ways one can interpret the first sentence, and even the first word.

To add another layer of complexity, Joyce sampled between 60 and 70 world languages in his wordcraft for Wake, including Japanese.

Page 5 of James Joyce (1882-1941), author. Yukio Suzuki [and others], translator. Finnegan tetsuya-sai. Tokyo: Toshishuppansha, 1971. [EL4 .J89f.Ja]

Japanese uses three forms of script—two syllabaries (or characters representative of syllables) called hiragana and katakana, and borrowed Chinese logograms (characters representing entire words) called kanji. For the sake of simplicity, think of their relationships like this: Hiragana (ひらがな) is used primarily for verb stems, miscellaneous native Japanese words and particles (sort of the equivalent to English prepositions); katakana (カタカナ) is used for foreign loan words, and kanji (漢字) is used for most vocabulary. You may see all three scripts in a sentence today, but for much of Japanese history, kanji was the dominant writing script.

Kanji took root in Japan around the 5th century CE and was adapted to the spoken Japanese language by the use of furigana, or rubi—hiragana that rested atop the kanji to denote the pronunciation of the character. Because Chinese script was “retrofitted” to Japanese spoken language, kanji are quite difficult to read, particularly for language learners. Some kanji have as many as five or six potential interpretations, depending on the context. Furigana were (and are) an essential component of understanding kanji in a Japanese context.

The Meiji Restoration, which was a period of great socio-political change after Japan opened itself to trade with the West in the mid-19th century, sparked debate as to the best method of modernizing kanji usage. Some scholars, like bureaucrat Maejima Hisoka—founder of Japan’s first postal service—advocated for the abolition of kanji in favor of a more simplified system. Others, like magazine publisher Nishi Amane, pushed for the use of romaji, or the Roman alphabet. In fact, his was also the official position of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur, during the occupation of Japan post-WWII.

The Japanese government reached a compromise in the form of the Toyo Kanji, which whittled the approximately 8,000 kanji in use at that time down to 1,850 that were deemed essential. The government guidelines stipulated that any words that couldn’t be written with the included kanji should either be substituted with a different character or written in hiragana or katakana, and furigana should not be used in conjunction with the listed kanji. The Toyo Kanji list has been updated twice, expanding to 2,136 characters as of 2010. The use of furigana hasn’t gone away; today, it’s used mostly to denote the pronunciation of particularly rare kanji as well as in learning material for children.

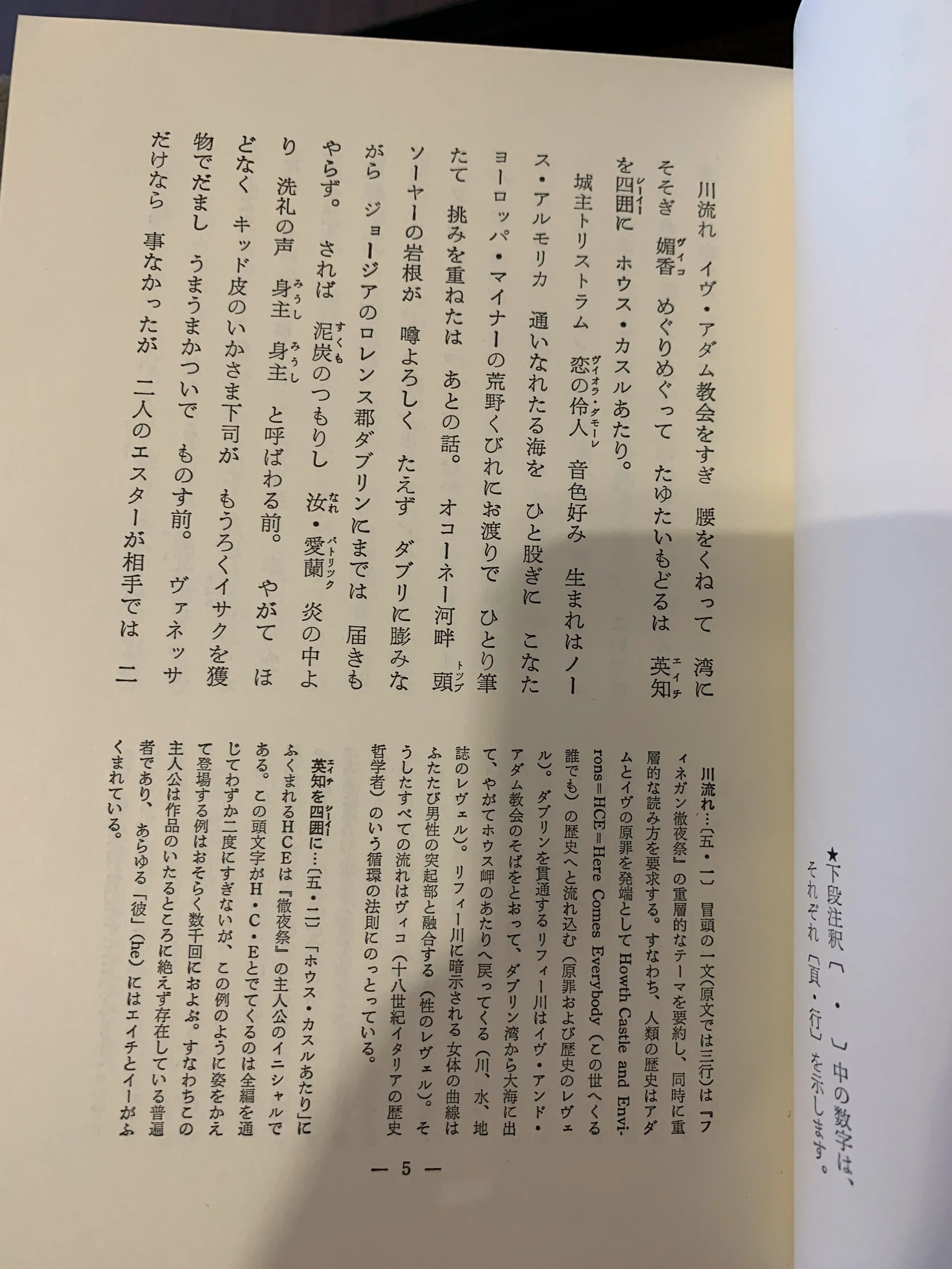

Slipcase for James Joyce (1882-1941), author. Yukio Suzuki [and others], translator. Finnegan tetsuya-sai. Tokyo: Toshishuppansha, 1971. [EL4 .J89f.Ja]

With all that setup in mind, let’s turn our attention back to the Japanese translation of Finnegans Wake. The Rosenbach’s edition of the Japanese translation was published by Tokyodo-shuppan, and was originally serialized in Waseda Bungaku, a literary periodical at Waseda University in Tokyo. The lead translator on the project, Suzuki Yukio, was a professor at Waseda and led a Finnegans Wake reading group. The Rosenbach’s translation is notable because at its date of publication in 1971, the Suzuki version was the most complete translation of Wake in any non-English language. Up to that point, most translations were focused on the Anna Livia Plurabelle chapter, which occurs near the end of this “book.” This includes the efforts of the Japanese translation.

One of the members of Suzuki’s reading group, Yanase Naoki, ultimately broke off to craft his own translation, quitting his job as a professor of English at Seijo University in 1986 to work on the project full-time. It took him seven years, but he produced the first complete translation of Finnegans Wake in Japanese: Part 1 in 1991 and Part 2 in 1993.

Although Yanase is credited in Suzuki’s translation, Yanase’s solo edition has become the touchstone for further translation efforts and is considered a masterful work in its creative use of language. I’ll use both the Rosenbach’s Suzuki translation and Yanase’s interpretation, which differ greatly from each other, to illustrate several cool linguistic concepts that make the Japanese version of Finnegans Wake so special.

One of the reasons kanji abolition didn’t come out of the Japanese language reform of the Meiji Restoration was that kanji is actually quite useful in communicating meaning. Each kanji not only has a pictographic meaning, but also a vocal pronunciation (or two or three) attached to it, and you can do some very interesting things with that interplay. One such literary device is a concept called ateji.

Ateji arose from the use of furigana in the Edo and Meiji periods, in which the author uses a furigana gloss over a particular kanji to imply a different pronunciation, and therefore a different meaning. Ateji was used as a form of satire because it could imply a deeper meaning from a seemingly mundane sentence. The use of ateji in this way fell off after the post-war language reform, but was used in Finnegans Wake as a way to match Joyce's creative use of language.

Here’s an example of ateji from Yanase’s translation of Finnegans Wake, using the first word, “riverrun.” It’s a compound word that points at a couple of different interpretations—the river Liffey as it cuts through Dublin, the sound the rushing water makes, and the swiftness of its flow. This is how Suzuki, et al. interpret “riverrun”: with the kanji for river (川) and the kanji for flow or current (流). The interpretation invokes this sense of the rushing river. In Yanase’s translation, he instead pairs the kanji for “river” (川) with the kanji found in the verb “to run” (走). Read together as a compound, it could be pronounced as “kawabashiri,” and that would be a valid interpretation. This reading invokes the phrase “iwa-bashiri,”, meaning “river flowing around rocks.” However, Yanase uses furigana gloss to create alternate phonetic readings of each of these characters. The furigana reads “sensou,” the phonetic word for “war.” The complete word, as Yanase renders it, hints at the war introduced two paragraphs later. Here is the full first line from Yanase’s 1991 translation:

In the next paragraph, we find the first of the ten “hundred-letter words” Joyce sprinkled throughout the book. These are also known as the “thunderclap” words, because most of them depict thunderclaps. These words are not only onomatopoeia, but they also contain words for “thunder” in other languages (including Japanese).

For reference, here is the first “thunderclap”:

bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk

And here is the translation from Yanase’s version:

ババババ ベラガガラバ バボンプティドッヒャンプティゴゴロ ゴロゲギ カミナロン コ ンサンダダンダダ ウォールルガ ガイッテへへへトールトル ルトロンブ ロ ンビピッカズゼゾンンドドーッフダフラフクオ オヤジ ジグシャッーン!

Ironically, the Japanese version is, in some ways, easier to read thanks to the syllabic nature of characters. Did you notice how the English version kind of runs together in a way that makes your eyes blur?

Yanase and the translators that came before him were able to make use of many sophisticated devices at their disposal to reinterpret Joyce’s vigorous bending of his own native tongue. I do say “reinterpret” rather than “translate” here purposefully, as the very act of translating Wake is not to translate in the traditional sense. Every word and phrase of Joyce's final book demands a degree of rigorous study and artistry to communicate across languages. Yanase’s translation, even from the first word, deviates greatly from the Suzuki version, because he chose a different interpretation.

If you are a bi- or multi-lingual reader and are interested in reading Finnegans Wake, I encourage you to seek out one of the 17 complete translations and use it as a resource. And if your target language has not yet been tackled, perhaps you could be next to take the leap in solving Joyce’s extraordinary literary puzzle.