“What is your favorite book?”

by Bryn Michelson-Ziegler, Assistant Curator of Outreach & Engagement

Bryn Michelson-Ziegler is Assistant Curator of Outreach and Engagement at the Rosenbach Museum & Library. She holds an MFA in Book Arts and Printmaking from University of the Arts and maintains active scholarly and artistic practices.

When getting to know new people, I love to ask the question, “what is your favorite book?”

What I’m hoping to learn is not their favorite story, although this may factor into their answer, but rather their favorite book-as-an-object. As someone who is surrounded by books every day, I am always curious to learn what people find meaningful about specific volumes. I’ve gotten a few memorable answers: a particular copy of Winnie-the-Pooh, chosen for the memories it carries of a childhood home; a leather-bound planner that serves as a daily companion; a grandparent’s cookbook that still smells like frying onions and potatoes.

My colleague David’s favorite book is from the Rosenbach’s collection. He describes it as an “autobiographical poem by a beleaguered Welsh Presbyterian minister, bound into a little book with marbled boards.” You can see a hint of these marbled boards, which are book covers adorned with a decorative swirling-patterned paper, in the photo below.

David Evans (1681-1751), Cãan drwstan gwynfan [aneglur]. Pilesgrove, NJ, [1747 or 8]. AMS 44/8

My own answer admittedly varies, but often it’s the tiny handmade accordion album where I hastily affixed my wedding vows just hours before the event. It starts out pocket-size, and when the folding pages spill out, the small volume grows tenfold.

Wedding vow book. Personal collection of the author

What is your favorite book?

As you ponder, I’d like to invite you into the creative field of “book arts.” Book arts can be challenging to define (not least because books themselves can sometimes be challenging to define... although perhaps that’s for another blog post), but here’s where I like to start: artist books are works of art that take the form of, or are inspired by, books, and book artists create books the way that painters craft oil portraits or photographers develop film.

So, how do we go about exploring books as works of art? Much of the time, we can treat books as vehicles for information with two simple components: the container and the all-important contents. Imagine pouring text into empty book covers, filling them like a coffee mug. Though we might be drawn to the beauty of a container made of leather adorned with gold or the convenience of an e-reader file, the information inside arguably remains the same.

However, book art invites book lovers to explore beyond the text for meaning. When we engage with books as art objects, we set aside the distinction of content and container, and consider the method of print, the style of the binding, and the language as equal ingredients of a complete, bookish experience. Book artists today use (and preserve) historic techniques that can be traced back through the Rosenbach’s holdings, including letterpress typesetting, engraving, hand papermaking, and fine binding.

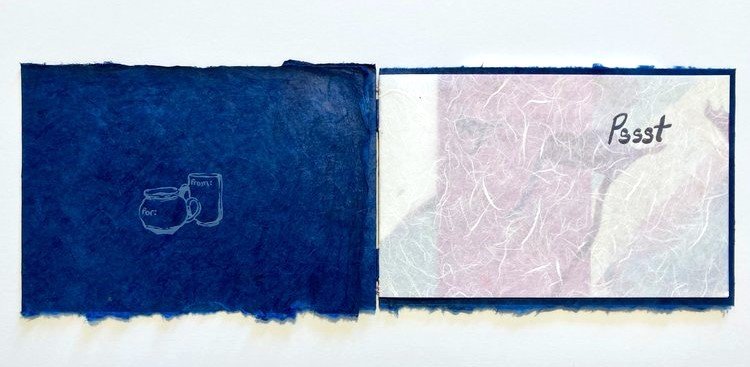

Here's an example of that process. I set out to make an artist book that felt like it was whispering secrets in the reader’s ear. In addition to signaling that feeling through language like “Pssst, hey—” I chose to make the first and last pages of the book a soft, translucent paper to bookend (if you’ll pardon the pun) a quiet, personal experience for the reader.

Book to Tell Someone You Love Them. Personal collection of the author

When we study rare books, we appreciate and interrogate the decisions and craftsmanship that formed (and altered) the objects in front of us. If picking up a copy of Don Quixote from your local bookstore offered the same experience as paging through the 1605 first edition, there would never have been bibliophiles like Dr. Rosenbach, who appreciated the craftsmanship of both container and content, or museums like ours which celebrate and share the unique history of individual tomes in our collection.

Here’s an artist book in the Rosenbach’s holdings that intertwines container and content to offer a new experience of a familiar text: a passage from James Joyce’s Ulysses. In Margary Hellmann’s three-dimensional book, Joyce’s words dance across wave-shaped pages, which project out like the choppy ocean. My favorite detail is how the text placement encourages interaction with the book, as readers have to move back and forth for each line of text. The story moves as though it is pulled by the tide: crashing to shore, receding, and then tumbling in once more.

Margary Hellmann (1935-2012), Wavewords from Ulysses. Seattle, WA, Windowpane Press, 1996. EL4 .J89wa

When I read Wavewords from Ulysses and trace the unusual evolution of text, I am reminded of another Rosenbach treasure, the manuscript of Ulysses. A portion of the manuscript is written in a blue notebook, where Joyce composes episode 17, “Ithaca” before flipping the book over and starting from the back cover to draft episode 18, “Penelope” almost, but not quite, meeting in the middle.

In addition to the manuscript, the Rosenbach holds numerous copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses, and each volume (or “container” for this incredible text) has something distinct to offer. When I think of how emphatically Joyce pursued the now-unmistakable blue of the first edition covers, I think of book arts, where you are encouraged to judge a book by its cover because the cover is just as much part of the message as the text, the images, and the thread holding it all together.

James Joyce (1882-1941), Ulysses. Paris, France, 1922. EL4 J89ul 922a

At the Rosenbach, we are building a dynamic roster of book arts programs, because the subject offers new ways to experience the museum and library. Through book arts, you can explore the material history of our holdings, celebrate the craftsmanship responsible for fabricating our treasures, and understand our collection through making your own unique books.